• This is a free post, but almost all of my content is now behind a paywall. I have explained why in this pinned post

The Free Content Dilemma

I started my Substack back in September 2021. It was at a moment when I was going through a difficult time in my career, finding it increasingly hard to make ends meet as a single income (parent) household, in an industry which is not particularly well-known for rewarding its creatives just the celebrity authors.

Please upgrade to support my work

Three years ago, in the depths of the Covid pandemic, I started writing a novel. It was a time when travel was forbidden and so, from my kitchen table, I took a trip two and a half thousand miles away to Turkey, and a place called Bodrum — some of you may know it.

In my twenties I lived there, it was an unusual place to end up, a strange sounding language to get stuck in the head of this sarı kızı— this blonde haired girl.

The year before that had seen a huge change in my life, my father had been ill for many years after a series of strokes left him disabled and he had died of a massive heart attack just nine months after I had married the boy from the village where I had grown up. Something about realising my own mortality had made me understand I needed to leave this new husband, to swap him for an adventure in the world.

It had devastated both of us when I left him, this best friend that I had married, yet with a tiny inheritance from my father of not much more than ten thousand pounds I had set off on a journey to mend my own broken heart. After many months living out of a borrowed backpack I had washed up on those Mediterranean shores because I wasn’t ready to return to England having thrown away the only life I had there. While I had been working on magazines in London the year before I had travelled to Bodrum on an assignment and made friends with an English woman there who found me a little apartment to rent — someone who is still one of my closest friends to this day.

The apartment was in the less touristy, more Turkish part of the town, in the marina, down some backstreets where if you climbed to the top of one of those sugar cubed houses to hang washing you could spot tall masts of gulets rocking in the setting sun.

My little studio apartment was up some stone steps, and my landlady Zeynep Teyze lived below me in her two rooms.

She was perhaps one of the richest women in that town owning many seafront properties, though she dressed like a villager with her billowing cotton trousers and headscarf — a throwback to how the town had been to her as a young woman when it was more of a fishing village, when there was no road packed with traffic and hooting horns, instead there was a small stretch of sand that reached all the way to the front steps of the houses and the olive oil factory that stood overlooking the sponge boats and their divers.

Here is a photo of my landlady as a young woman with her three sons, forgive the poor quality.

Each of those sons had grown up and had families of their own when I arrived in Bodrum and moved into my little apartment in exactly the place where this old black and white photo was taken. Each of them lived in the houses that surrounded the courtyard garden which was filled with yellow courgette flowers, bright pink bougainvillea, and fecund with aubergines. The air smelt of dill, parsley, mint and thyme, and a cockerel pecked a the dry earth and woke us up before the call to prayer from the minaret each morning.

I loved this simple life that I had, saving my shower water to flush the toilet, riding around town on my pink bike, and being fed stuffed vine leaves by Bakiye, the wife of one of my landlady’s sons who, despite the fact we had no shared language, became one of my dearest friends.

They looked after me, when the heat at the height of summer (and the icy air conditioning of shops and restaurants) made me sick, they would send me to the pharmacy with a note for some dried herb tea to make me well again. When a fever left me delirious and in bed for days, I was aware only of the soft pad of my landlady’s footsteps up my stairs and her wrinkled palm on my forehead to check my temperature. When I stepped into their home and forgot to put slippers on, I would be scolded that my eggs would go cold without them, and quickly sent back to the door. I loved these people, finding them had been a gift and they mended me.

In August when the temperature at night refused to dip much lower than forty, we would leave the bay on their fishing boat and sleep on top of the deck underneath only a blanket of sky knitted with bright stars. Once we took the boat out for a week and lived off the sea: samphire, freshly caught sea bass and octopus, and once a swordfish so big caught in the ink-black nighttime water that we ate it for breakfast, lunch and dinner for days. Without a shared language we instead pointed at pages of a dictionary to understand each other, until my grasp of Turkish meant that we could laugh over shared jokes and understand our life stories better.

It was the happiest time of my life. But life moves on, time changes, back in London my work took over, then I had my daughter, got married, a bad relationship sucked up a decade of my life, and though I hadn’t forgotten about these good friends, I didn’t have the opportunity to return to them. Writing that book meant I could.

I wrote it quickly, in a matter of months so keen was I to return to Bodrum, these characters I had created poured from me as if they had been waiting forever for me to tell the story of this town I loved. I think now looking back I wrote it too quickly, was too much in love with it — and so excited to return to that time — that I overlooked its weaknesses. I expected everyone else to feel the same about it and it did go out on submission but failed to find a home. But just like the memory of my friends it refused to leave me, and so this summer I returned to complete my research and to reunite with those people I loved, and yes, redraft that novel.

I was scared though, worried that the town and peninsula I loved would have changed so much that I wouldn’t recognise it — or perhaps my friends wouldn’t recognise me. I have spent my daughter’s life telling her about this place, and perhaps she has caught glimpses of my love for it when we have eaten in Turkish restaurants and I have taken the opportunity to chat to the waiters in the only language that has really stuck in my head, a language that feels pretty useless most of the time, especially when I have spent much of the last few years holidaying in the south of France.

Yet here I am in Turkey, writing to you from a balcony that overlooks a deep blue sea, and just in the distance, the soft outlines of mountains that are almost swallowed by the misty blue of the horizon.

Fifteen years it has taken me to come back and what has changed? The place, definitely. The population of Bodrum has multiplied three or four times since I lived here, there are not homes that ring the horseshoe shape of the harbour now but shop after shop, bar after bar, restaurant after restaurant, shiny glass and neon lights. Even in the backstreets, as I walked to my old apartment, tiny spaces have been filled — a boutique pansyon here, a courtyard bar there. And then I came to the entrance, the place where stray dogs would leave me after they had walked me home in the early hours of the morning when I was 25 and lived alone in this town. I snapped a photograph of my daughter outside the gate.

I walked down the alleyway and was immediately struck how time had changed, the central garden didn’t feel barren as such, but not as fertile, not as lush and green, there were no fat purple aubergines hanging heavy on stalks, there was no cockerel scratching at the ground, and no Zeynep Teyze coming out of her little house and holding her hand out to me so I should kiss it with my chin and then my forehead in the traditional way of greeting your elders in old times. But then I knocked on Bakiye’s door, she had moved downstairs now since her youngest son who was eight when I met him married and moved into her apartment (he’s 32 now). Downstairs Bakiye pulled opened the door and we exclaimed in unison in Turkish, in shock and delight: ‘you’re exactly the same!’

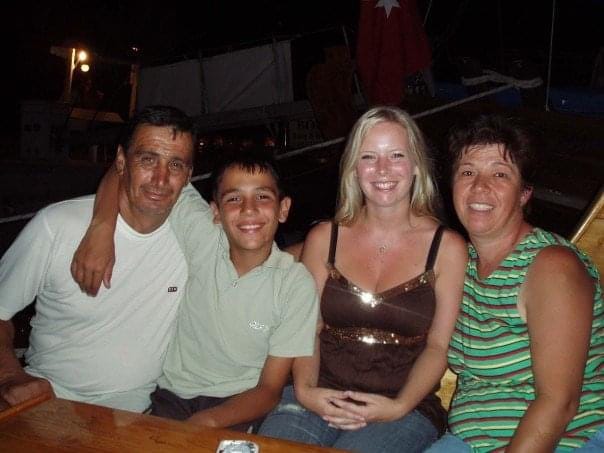

Here we are again all those years ago:

Me and my daughter took off our shoes and she ushered us inside, no more talk of our eggs going cold (I mean, mine have almost run out now anyway). I introduced her to my daughter, having quickly prepared her on the way how to greet Bakiye should she offer her hand to her as Zeynep Teyze did to me, and Bakiye laughed and said that was the old way, that was her mother-in-law’s way. I knew Zeynep Teyze had died seven years ago, but suddenly I missed the old way, and so my daughter greeted her like that for old time’s sake.

Bakiye insisted we sit down at the dinner table which was filled with a rocket and lettuce salad, five or six whole fried sea bass and a plate piled high with calamari. My daughter’s eyes lit up at her favourite food and Bakiye and her husband, Hüseyin Abi kept telling me to tell her not to be shy, to eat more and more, just as they had me twenty five years ago.

Outside of that house, in the harbour, so much had changed in Bodrum, but around that table time stood still, the smiles as warm, the hospitality was just the same.

Ibrahim — their son who was around 15 last time I saw him — came home with his new wife. He is now a captain like his father and his father’s father before him. He told my daughter I was his first English teacher. I remember black nights on the boat when he would point up to the silvery moon in the sky and ask me the English word.

“Moo… moo… moon,” he would say and we would collapse into giggles as he sounded like an inek. Now he can speak to my daughter in English.

The following night we went and sat on his new boat, not the same little fishing boat that we used to go out on during hot Bodrum nights, but a grander wooden boat with sails and three double cabins and we talked excitedly about going out for a week with him next year (incidentally please let me know if you would like a holiday with him).

We ate the baklava that I had bought and drank the cherry juice and I asked Hüseyin Abi how Bodrum had looked in the 1960s when part of my story is set. It was him who told me about the olive factory — today it is a tattoo parlour. We talked about Karaada (Black Island) that faces Bodrum and where, all those decades ago, people from the town would take their summer holidays, sleeping like sardines, all arms and legs, in the one building on the island. Hüseyin Abi told me that even now, just after dawn, donkeys come to drink from a spring of fresh water on the shore, and they call to their friends who come to join them, and the sound attracts jackals and foxes, and eventually they all drink together as the sun rises.

There is still magic to be found here.

We posed for photographs just like we did all those years ago before we had digital cameras and could see them instantly, and Bakiye and I grabbed my phone and pointed to all the bits of us we didn’t like and moaned about how much weight we’d put on over the years. When I pointed at my chubby arms in the photo she grabbed them and said ‘maşallah’ and we laughed and instantly forgot all about the bits of ourselves we didn’t like.

My daughter and Bakiye couldn’t communicate directly, only through me and yet I saw how they instantly loved each other as Bakiye sat there and plaited her hair. She told me to leave my daughter there with them and return to England alone and when I translated to her she said it was too hot and Bakiye was quick to remind her that they have air conditioning at home now.

We left the boat with promises not to forget each other and not to leave it fifteen years next time. If I do then I will be slightly older than Bakiye is now, and she will be in her mid seventies. Time passes so quickly, everything changes, the town changes but the people are the same and this is where I find my love for the place, still, after almost three decades.

I still have more friends to see, we will exclaim— as the rest of us have — ‘you’re exactly the same!’ As I wrote to one friend after seeing him, perhaps good friends always stay the same in one another’s eyes despite the passing of time.

I will come home from here reinvigorated to finish my story, more sure of so many parts of it and longing to see my friends again, to keep my promise not to leave it so long.

The first time we left Bakiye’s house, my daughter said she was going to stay up all night to learn Turkish so she could speak to them the next day. I’m pleased that she has seen how language — shared words — open up the world, that they help us make friends that last a lifetime, hopefully she’ll pay more attention in her French and Spanish lessons now. But seeing Bakiye and my daughter together reminded me of when I first arrived in Bodrum, how I would point at a fork, a spoon, a mirror, a table, and ask: ‘bu ne?’ — what’s this — and Bakiye would repeat that word to me in Turkish.

Words are my thing, they are how I have made a living since I was 18, and yet we didn’t need shared language then to make lifelong friends. We had eyes and smiles and we spoke to each other through the heart, and that was enough to keep me coming here for the rest of my life, and setting a novel here to pay tribute to the place that I was lucky enough once as a young woman to have called home.

Not because I was sad but because it was so true and of course so beautiful like all your writing xx

Ann. I had goose bumps all the way through this. Then I cried!!! Love mum ❤️