Can You Tell A Story Without Context?

Or, do I dare to riff off politics to teach you something about storytelling?

If you can afford it please consider subscribing to my newsletter for just under a pound a week. Your support really does make a difference to me – I’m always super excited when someone upgrades! Plus paying for good writing gives you benefits too like access to my entire archive including writing craft essays by more than 25 authors, and you get to join my monthly online creative writing club – I hope to see you there!

This weekend I watched a Channel Four interview by news presenter Krishnan Guru-Murthy with Israeli government spokesman, Eylon Levy.

Now, I’m going to tread a really fine line here so as not to upset anyone because I know there are strong feelings on both sides, so you’re going to have to trust me – stick with me – as there is something about storytelling here that I want to explore without getting into the politics of the current conflict.

When Krishnan Guru-Murthy attempted to speak about events preceding the atrocities on October 7th, Eylon Levy very quickly interrupted him to warn him not to ‘attempt to contextualise’ the events of that day.

The news presenter took that warning and moved on. But it got me thinking, contextualising something is not excusing it. At best, giving something context should give us a deeper understanding of a situation, and hopefully some balance.

Now I, like many of you, hope these current events will quickly be consigned to history, but should our history come without context as Levy suggests? Does that therefore – and must it – apply in all cases? Or does only one side get to choose whether there is context? For example, how would we possibly understand the need and desire for the state of Israel in the first place without the devastating context that came before it?

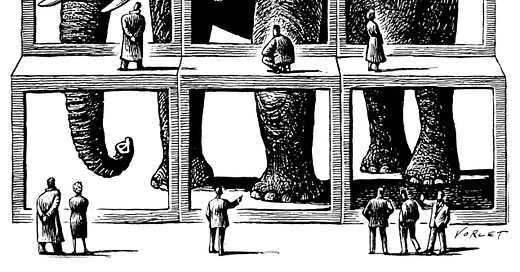

And what can this teach us about storytelling? Storytelling and human nature? Can story exist without context? Let’s have a closer look.

In answer to the question ‘what is plot’, EM Forster famously had this to say in his book, Aspects of the Novel:

‘The king is dead and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king is dead and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot.

The point here is there is a causality, there is context as to how the queen died.

Forster continues:

‘The queen died, no-one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king’. This is a plot with a mystery in it. A form capable of high development.

But there is still context.

When I was studying for my masters degree in creative writing, I was taught by Henry Sutton who often quoted these very lines from Forster to us.

In his excellent Crafting Crime Fiction, he includes a quote from PD James which takes this idea a little further in terms of storytelling:

To that I would add, ‘everyone thought that the queen had died of grief until they discovered the puncture mark in the throat.’ That is a murder mystery…

Again, it’s adding context to the scene where the queen’s body is discovered. If we now want to find out who the murderer is we’re going to need some more context, and to get that context, we’re going to have to wind back to the beginning of the story – probably to when the king was alive, maybe to a time when they were happy newlyweds. Ooh, I’ve just thought, might it be that something happened in their marriage to sour it? Oh my god, could it be that the queen murdered the king and then killed herself?

Ok, ok, I’m getting carried away a little here, but just say I’m onto something, don’t you think then we need to follow their story as happy newlyweds? Won’t we need to see what event it was that soured their marriage? Don’t you think we need to give this story context?

I’m trying to think of a time in storytelling – or in life – when context is not necessary. Could we live by Eylon Levy’s warning not to attempt to contextualise events? Is it possible?

So let’s look at life: my eleven-year-old daughter recently started at an all girls’ school and I cannot tell you the amount of drama that she brings home. Wait, no, I’ve just accidentally given you some context. Forgive me, I’ll start again.

So my daughter comes home from school and she is moaning about something some girl said or did. How do I help her navigate this problem without seeking out some context? What did the girl say? Why did she say it? What were the events leading up to her saying this? Had you said anything first? What’s this girl’s home life like? Ah… here we get a little closer to the story, but we did that by giving it context.

So that’s life, but what about professional storytelling?

At the moment, I’m writing a book proposal. In this would-be book (this is non-fiction by the way), the protagonist – a woman – kills a man. That’s it. That’s the story. I’ll send that off to the editor, shall I?

Of course, I’m being ridiculous. Let’s look at it further. This woman kills a man because he harmed her children.

Now this is a plot because I’ve added some more context.

Let’s add some more and see what happens to the story – does our empathy or understanding for this woman deepen or do we still see her solely as a killer?

This woman kills a man because he harmed her children. Worse still, he got away with it and was released from police custody to live next door to them again which made her children terrified.

I’m going to add another layer now, see how this makes you feel:

… she could not move house to get away from him because she was a single mother of five boys and life had always been hard and she had only just been given her first real home by the council. Now that this had happened, the council refused to move her and said that there was nothing they could do. And then she discovered this man had dozens of previous convictions for harming children and none of them felt safe.

Now I’m not asking you to forgive this woman, you might still just see her as a killer. As I said at the beginning of this piece, adding context does not excuse, but it should deepen our understanding of the human experience, our motivations, of the complexities of the decisions we make, or how – when our backs are against the wall – we deal with issues of right and wrong.

This is storytelling.

Think of an event in your life when you have done something you are not proud of, something that makes you feel ashamed even now. Don’t worry, you do not need to tell us in the comments, just personally, privately, in your own thoughts. In fact, pause reading this to think. I’ll wait...

You might have found, even as you thought of it, another image or story popped into your head – the reason why you did it, or the excuse. The context according to you, if you like.

Let’s imagine, one morning in a cafe, you poured your cup of hot coffee over someone’s shoulder who was sitting down and you ruined their brand new coat. You still feel so bad.

Oh but look what you immediately remembered, that someone had nudged your elbow and knocked the drink from your hand, but then if you hadn’t been in such a hurry that day, you might not have been pushing past people to get out of the cafe and get to work… right? But then you had to rush because you were late the day before and you didn’t want to get sacked because you needed that job.

Imagine telling someone that story of you dropping coffee over someone, but not giving it any context. It is not human nature to do that because none of us wants to think of ourselves as the bad guy — our psychological survival depends on it. It is the same for the characters we invent, or even those we come across in real life.

I wanted to set you an exercise, to write a story with no context. But you can’t. Context, as a storyteller, is everything. Imagine memoir with no background. Imagine a murder mystery with only the dead body and not the killer. Imagine a romance novel with no idea of events preceding how the couple eventually got together.

Context is, what happened next, and what happened next and what happened next… and so on. Or before, whichever place in time you are working from.

In Henry Sutton’s book he quotes Boris Tomashevsky’s essay Thematics, which came out two years before Forster’s lectures but was not translated until the 1960s.

‘His premise,’ Henry writes, ‘was that plot was an entirely artistic creation of ‘story’, stating: “The development of story may generally be understood as a progress from one situation to another, so that each situation is characterised by a conflict of interest, by discord and struggle among the characters.”’

Henry goes on to quote Aristotle, (and honestly, Henry is such a brilliant teacher and you really should buy his book if you are interested in crime fiction):

‘Aristotle’s Poetics established the dramatic framework around a beginning, middle and end. He was quite clear all those centuries ago that ‘incidents’ are the raw material of drama (or story), while ‘plot’ is the abstract concept referring to the organisation of the incidents. Interestingly, the same incidents can be organised in different sequences, with each different arrangement resulting in different ‘plots’. Story, to summarise Aristotle, is the natural chronological order of events before the storyteller turns them into plot.’

Our job as storytellers is clear, and without context we are, frankly, redundant.

And so, even though others – including the world’s politicians, or at least their political spokesmen and women – wish it weren’t so, whether in life or in fiction, I’m afraid there’s no getting away with it, context really is everything.

If you have found this post interesting, I would so appreciate you sharing it so others can enjoy it too — I rely on my lovely subscribers to help me find a bigger audience. Just click the button below.