Last week I wrote a book proposal. I’ve had the idea for many, many months, but something had been holding me back: planning.

Now, this is the thing about planning, it can be extremely useful, it has its place, but it can also be known by another word beginning with ‘p’…. and that is procrastination.

I wrote about this in a piece two years ago, and I mentioned this essay to White Ink members who attended my creative chat last Monday.

Here is the link to this piece, and I’ve removed the paywall so that everyone can read it:

Research*, the Procrastinator’s Bestfriend

Why do I have a photograph of a kitten illustrating today’s post? All will become clear. For now, we’ll call it research. It’s been an exciting week for sales on Wendy Mitchell’s new book, What I Wish People Knew About Dementia. More on that soon. Regular readers will know that I am Wendy’s ghostwriter, and if you missed it last week, you can read more about how we worked on her first memoir,

This piece mostly focuses on research, but research/planning, they can be one and the same, especially when both are trying to keep us from the page. So how much is too much? And where is this line between planning and procrastination?

As I told White Ink members last week, I have tried things all ways. For example, when writing my novel, The Imposter, which took me seven years to write (mostly because I had to keep picking it up and putting it down while I wrote other people’s books), I planned and planned, I had those little notecards on a pinboard, different colours assigned to different characters, a way to get from A to Z of my plot via stepping stones all laid out for me, and I found it just so completely uninspiring. I found that I had told myself the story in those little notecards, when actually I should have been telling it – or rather letting it reveal itself to me – on the page. It was actually on the page, seven years later, that the final and biggest twist came to me.

Now, I know this is how some writers always work, in fact, Sophie Hannah, domestic noir/mystery writer extraordinaire, claims planning is her foolproof method, the reason that she is as prolific as she is. (For those who would like to hear more from Sophie, she guest authored an essay for White Ink here).

Here’s what she had to say about planning: ‘The main reason I’m a planner is that I really enjoy doing it. It makes life so much easier for a writer, and it gives you something concrete to look forward to.

‘Without a start-to-finish plan of what’s going to happen in my novel, I don’t know for certain that the idea is viable. It’s by writing a chapter-by-chapter, scene-by-scene synopsis that I put this to the test.’

Sophie claims that if you get the planning bit right you should only need to write one draft of your novel, which is a rather enticing offer.

Is Sophie’s prescriptive scene-by-scene planning the secret to her success? And, I wondered, is this mostly necessary when it comes to writers with plot-heavy novels.

And then came along a few curveballs in my research on planning for this month’s theme, Stephen King, for example, says he never plans and describes plotting as ‘incompatible with the spontaneity of real creation.’

PD James, another novelist who relies heavily on plot, says even she doesn’t know herself who the killer is in her whodunnits until the end.

Patricia Highsmith believed in the ‘incomplete plot’. She said: ‘The story must be alive while the writer is writing it. It, sometimes, need not even be complete because it should still be entertaining the writer.’

Margaret Atwood described overplanning as leaving yourself with something akin to a ‘paint by numbers’ novel, and I tend to agree. For me, there was just not the enthusiasm to write once I had already told myself the story, and I believe this can show in the writing — you must keep the air in the balloon and you can only do that on the page.

Although that is not to say Sophie Hannah is a wrong when she says that planning lets you know if you’ve got a viable idea in the first place. A certain amount of planning, but vitally not enough to keep you from the page, to give you the fear of the page because what you’re imagining what you’re going to write is nothing, at first, like the reality.

It is a dilemma. But it is one that you can only unravel yourself by doing the work, and I know plenty of writers whose books get written by them being both ‘a planner’ or ‘a pantser’ – as non-planning appears to be known in the trade.

You can often find if you have a very plot-heavy novel and you are trying to wrench that plot into various twists and turns as featured on your pinboard of notecards and scene-by-scene breakdowns, that the reader can feel manipulated by the writer, they can spot the devices that you have used, and they don’t like it. It’s something to look out for.

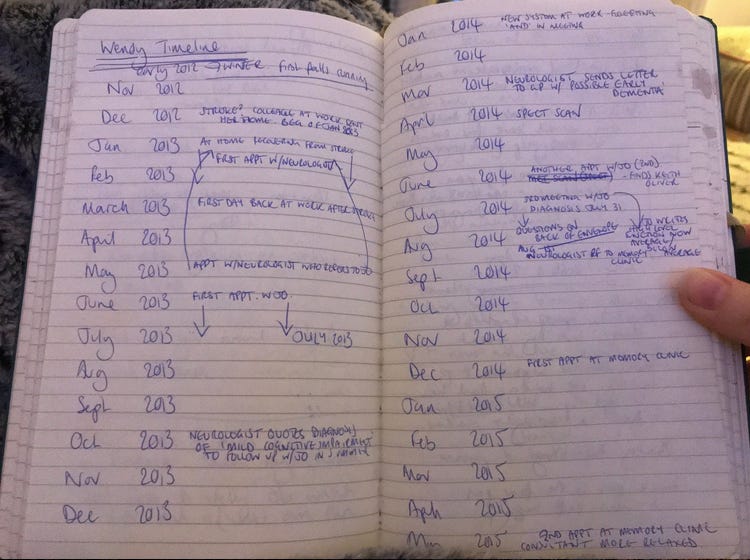

Up to this point, we’ve mostly discussed fiction, and I thought you might like to see what planning looks like when it comes to non-fiction. The other day I found in my files a diary entry I was attempting to put together when Wendy Mitchell and I were writing her first memoir, Somebody I Used To Know. I had a gap of around two years just before Wendy was diagnosed with dementia that I needed to fill with where she had been, what she had been doing, and what symptoms she was experiencing. And I needed to break this down month-by-month so the story was seamless. This was all before she had started writing her blog, so we did this in the end via various media including hospital letters and even her daughter’s diary entries.

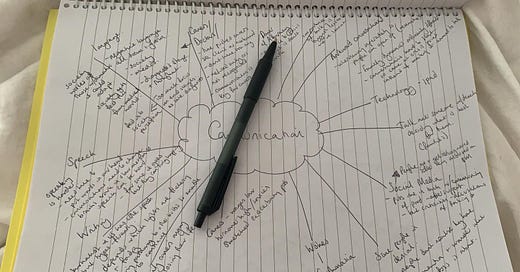

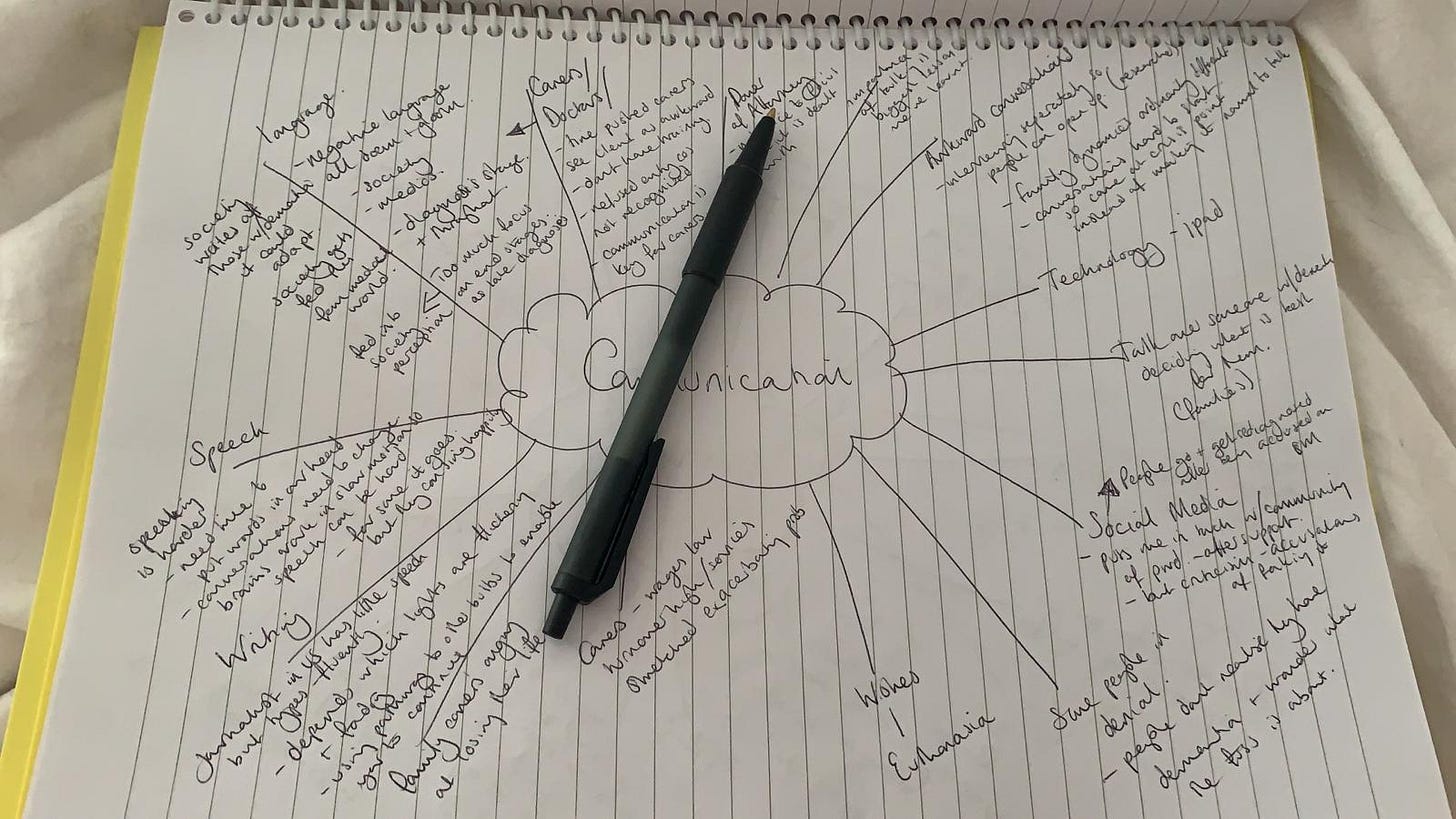

For the second book What I Wish People Knew About Dementia, we did our brainstorming for each section over zoom, me sat ready with a pen and paper and drawing a great spidergram. Here’s what our communication chapter looked like in it’s early days.

Planning is vital when it comes to non-fiction because in a proposal you are going to need to demonstrate to the editor where this book is going, what its central arguments are, and you’re going to need to have started on that research to know if you have any big reveals in there – and big reveals are worth paying big bucks for, so you don’t want to discover this halfway into your writing once you’ve already done the deal with the publisher.

Memoir, of course, is slightly different from non-fiction, in that it is the process of writing the book itself that will reveal what the actual journey is for you, the writer. I know that Lily Dunn does not recommend writing a proposal for memoir until you have written the book itself, and for good reason, particularly when it comes to very personal writing – how do you know for yourself that you want to share this material with others before you’ve even stripped away the layers and got to the nub of what you’re trying to say?

And yet, when I write proposals for memoir for other people, I’ve never finished writing the story first, it is my job as a ghostwriter, to spot the nub of the story and articulate that into words before the process has begun.

You can see that it’s complicated, and each person, each project, requires a different approach.

The proposal that I wrote last week was for a memoir of my own. I have not finished writing this book – as Lily recommends – but I have a good idea of what’s going in it, and it has been living and breathing in my mind for a long time.

Perhaps the first rule is there are no rules, maybe the rule is that there is only what works for you, as a writer. And to discover what that is, there is no getting around it, you’ve got to get yourself in the chair, you’ve got to get yourself writing. You’ve got to stop thinking about it, and start doing it.

But my biggest advice is, don’t let planning become procrastination.

Please consider upgrading to become a paid White Ink member for more posts like this one, it really does mean a lot to me making my living as a writer and there are lots of benefits for you too, like hanging out with me at my kitchen table on zoom once a month and discussing various aspects of writing craft and life (last month’s theme was ‘place’), a whole archive of more than 25 guest author essays on writing craft, plus dozens of essays on my life, too. And, as you can see below, White Ink is a Substack Featured Publication 2024 (twice in fact!) so it’s worth it for the price of one coffee a month.

If you are sincerely struggling and really do not feel you can afford a few pounds each month, then please do email me as I wouldn’t like anyone to miss out, and in return, with no questions asked, I will gift you a complimentary membership.

Email: annawharton@substack.com

I am definitely a panster. I tend to agree with Stephen King and Margaret Atwood that planning takes away the joy and the surprise and if you as writer are not surprised then how can you expect your reader to be?

I was interested in what you wrote about ‘the big reveal’ - I guess this doesn’t apply so much to memoir. Although in the writing of memoir a writer should get better understanding, so the reveal should be better wisdom … the satisfaction of attempting to answer difficult questions.

Great piece, and I love seeing people’s process in their notebooks

I’m definitely a pantser. I found this really interesting in your session last Monday Anna, as I currently only write non-fiction, and although I have a ‘plan’ for my book proposals, it never turns out to follow that plan!!! My proposals become a work of fiction in themselves 🤣. I have an idea of where it will go, but as my books are story driven and very ethnographic, there are twists and turns that I don’t anticipate until I’m deep within them. I think for lesson- driven non fiction planning would be much easier. Perhaps this is why I find the book proposal so difficult! I do love to mind map, and have post it notes in theme areas so there is a kind of process, but I think my ADD brain just does not lend itself to planning in a rigorous way. It’s a challenge!